Holocaust

“Since I fear God, I hesitate to highlight anything which might throw coal on the fire, then even the making of unconscious errors weighs just as heavily as Evil…I tremble before the fanatics‘anger, while they are ignorant and imprisoned by the chains of evil stupidity..”

(Nachman Krochmal)

HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL BERLIN

by Gabor Török, Frankfurt/Main

Every monument represents always as much the personal expression of its creator as the content of its meaning as monument. Therefore a few words to explain what moved me to create such a monument.

To create a monument to the holocaust is a personal challenge for me, since I count both Germans and Jews among my friends. I appreciate therefore both sides and note that neither can give word to the certain tension which exists between them. I myself am neither German nor Jewish, having been born and raised in Budapest. I have been a German citizen now for 11 years. I have been living already 18 years in Germany and, as an artist, have come to know German society in all its facets. I learned to appreciate this country as a lowly asylum seeker and now, higher up the social scale. Differing opinions and issues are no strangers to me. As to the holocaust, I have always been ruled by my emotions. At some stage I began to ask myself why I – like most other people- had such strong emotions without really knowing the background.

The creation of a memorial always faces certain problems. They are created to commemorate a person or an event. The political and societal norms prevalent at the time of the monument’s creation may be very different in the future. These norms change, just as artistic taste does over time. The place remains but knowledge of the events and the degree of personal involvement in those events, evolve over time.

He who wishes to create a memorial, must be aware of these changes over time. The monument should be universally valid and readily comprehensible, otherwise there is a danger that it may be forgotten or become a cliché, or in the worst case, may be misused for political ends.

The holocaust cannot simply be described as merely a war event nor can it “simply” be dealt with by stating that 6 million Jews were murdered. Each single one of these 6 million people had to die by himself; each one is an individual, horrible death.

After more than 50 years since the holocaust, our views on religion, society, art and culture have changed entirely. Two generations have followed since then. There have been numerous artistic attempts to come to terms with the subject visually, always from the respective current viewpoint and location. In most cases, the focus was the immense pain, the crime, the trauma; not however the disease or its cause. This was probably correct from the respective previous points in time. But the situation now is different; many things have changed in the past 50 years.

Only since German reunification is the war completely and finally over. The past can no longer be changed; we must live with it. Our responsibility today is for the future.

A holocaust memorial in today’s Berlin must not pander to political, religious or personal interests. And it most certainly should not take into consideration personal sensibilities.

Such a memorial should not seek to satisfy Jewish emotional expectations nor the German guilty sense of duty such thereby contributing to “ok that takes care of that then”. Likely this will be the last holocaust memorial to be erected in Berlin. Therefore it should concentrate on the essence, not be open to manipulation and be easy to interpret. This memorial claims, with reverence, to reflect all the weight and pain and symbolically, from Germany, point to the future.

It would be presumptuous to believe that human pain can be reflected in art. Today, saying 6 million murdered Jews almost appears like a cliché and does nothing to address the personal suffering and the psychological burden of the victims and their offspring. That “the Germans” murdered these 6 million Jews is also a cliché and does nothing to explain the psyche of the murderer.

Such a rounded inaccurate number is an invitation to trivialise and ignores the survivors who have “merely” lost their children, mother etc., or those who survive as emotional cripples. In order to grasp the effect of the holocaust today, it is necessary to examine and understand a personal fate. I have before me a photograph taken of a mother with a child in her arms at the very moment when a shot enters the back of her head at point blank range. There are therefore four people involved; the child, the mother, the shooting soldier and the photographer.

It is beyond imaging what the mother holding her child in her arms is feeling at that moment. Hoping to capture that moment as an artist would be pure arrogance.

And the role of the others – the shooting soldier or the photographer – there is no artistic value in examining either role.

Therefore, taking a similar theme would also be unsuitable for a memorial.

The death of 6 million Jews belongs to the past, but the agent of anti-Semitism is a latent part of our society. We must strive to ensure that the holocaust isn’t simply “cast off” as history, but instead show its omnipresence – especially when the last personal memories exist no more. The fiend inherent in man will remain and it would be foolhardy to believe that a holocaust could never happen again.

The holocaust was the final act in a long process, not a sudden overreaction. The above described photo depicts the finale of this process. Humankind could hardly sink much lower.

One thing we cannot do; we cannot begin to imagine the emotional state of the murdered mother. We can only commemorate from the survivor, the murderer and their respective offspring’s point of view. In contemplating the photograph, the view’s perspective is the deciding factor. If the shooting solder, the murderer, were my father, I would want to forget as quickly as possible. All things considered, I wasn’t even born and cannot imagine what could have caused him to do what he did. I would my lifelong ask myself if I share similar attitudes. I would certainly not have told my children, not wanting to burden them. It would however be totally different if the mother in the picture were my mother, the child in her arms my brother. I would never be able to forget and would never stop talking to my children and grandchildren about it.

Each of these viewpoints is human and understandable and is neither typically Jewish nor typically German. No half intelligent, self-critical German could say with any certainty today that he would not have participated. A Jewish person today on the other hand, certainly identifies with the role of the persecuted and believes he feels the constant sense of being under threat. At the time simply being Jewish, and he is still Jewish today, was enough to ensure persecution. Therefore both sides are marked by the past, though both bear the burden in different ways.

Anti-Semitism has always been a part of Christian history. Whether from belief or superstition, anti-Semitism existed, exists today and will continue to exist and cannot be ignored or changed; Judaism however survived. It lives on according to its own laws, traditions, morality and culture. Which leads to a very particular situation for those Jews living in Germany. They are German, but live in their own community as Jews.

When Germans however talk about Jewish people, those who have contributed to the advancement of German culture, science, or politics, this ambivalence is never mentioned; suddenly they are only Germans.

When Jews speak about Germans or vice versa, the “otherness” of each is not necessarily spoken about in a flattering manner. This is not usually personal, but follows a traditional behavioural pattern.

That is of course a gross generalisation, but nonetheless true, I believe.

People are not all alike, which of course is not anyway desirable. It is precisely the differences which make life worth living. But nonetheless therein lies a danger; the holocaust and evil in general build on these differences. Therefore the danger of anti-Semitism is ubiquitous and doesn’t require any particular circumstances to erupt. Often evil appears in the form of a “brilliant” idea, which was, let’s face it often propagated during the Third Reich. One of man’s most important responsibilities is to recognise evil. Evil heightens our senses. And so long as it is not expanding, we can tame it. But once evil has taken hold, we can no longer control it. Evil on the move has enormous destructive capacity. Therefore we must fight evil before it takes hold.

Description of the Monument

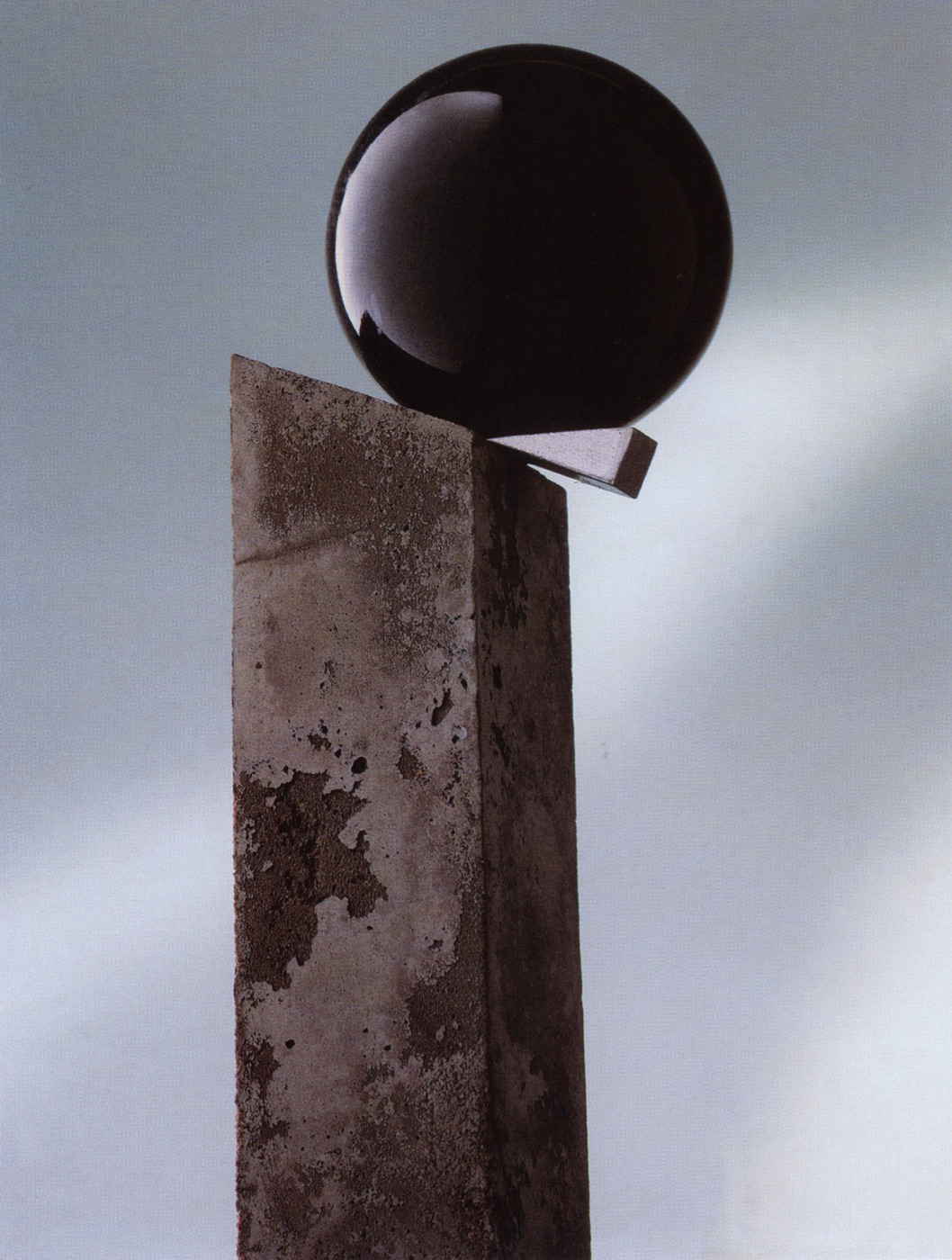

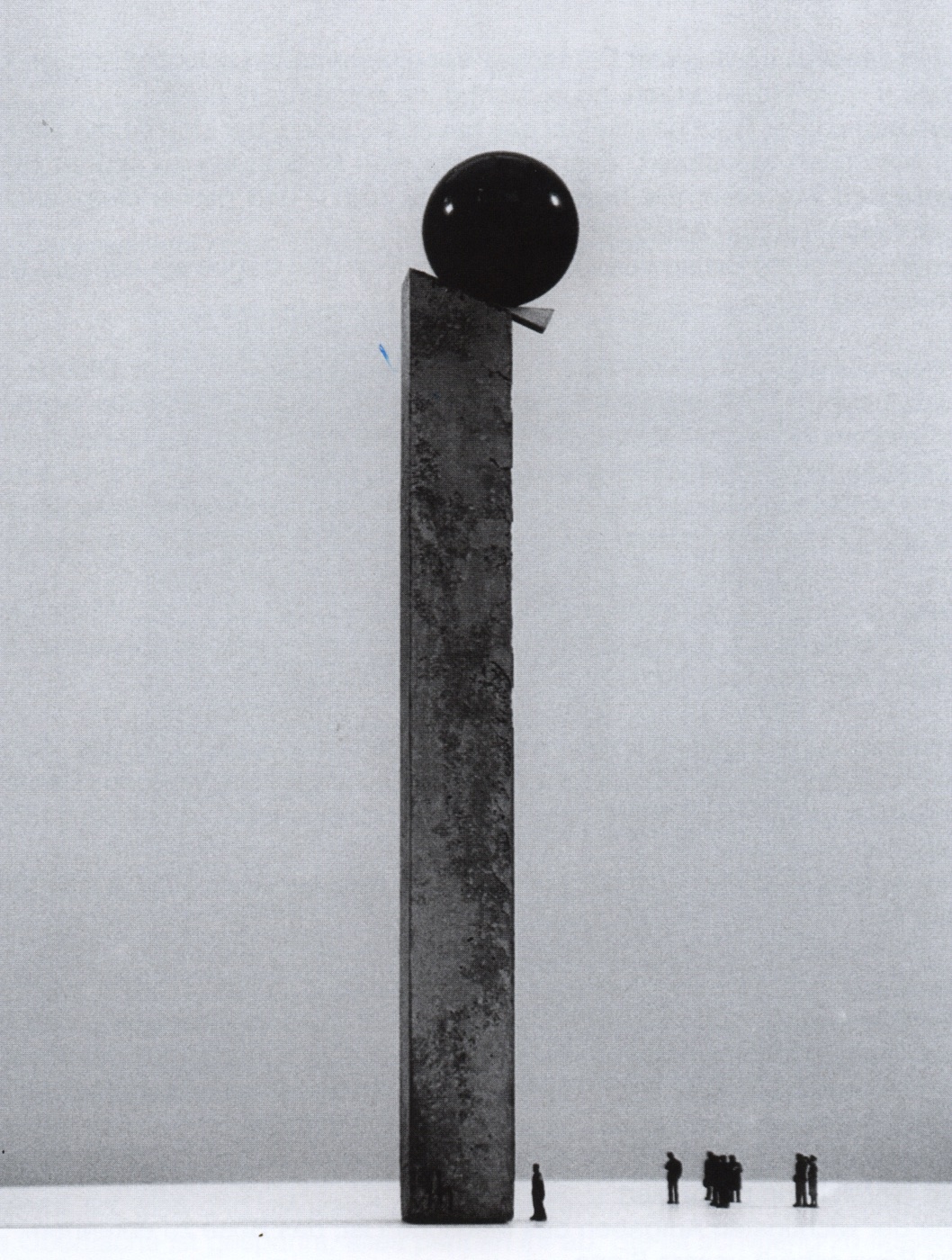

The monument consists of three pieces; on a high, sloped concrete column, a shiny black granite orb is placed, which threatens to roll down. A stainless steel wedge pushed between the column and the orb hinders its progress. However a sense of instability remains.

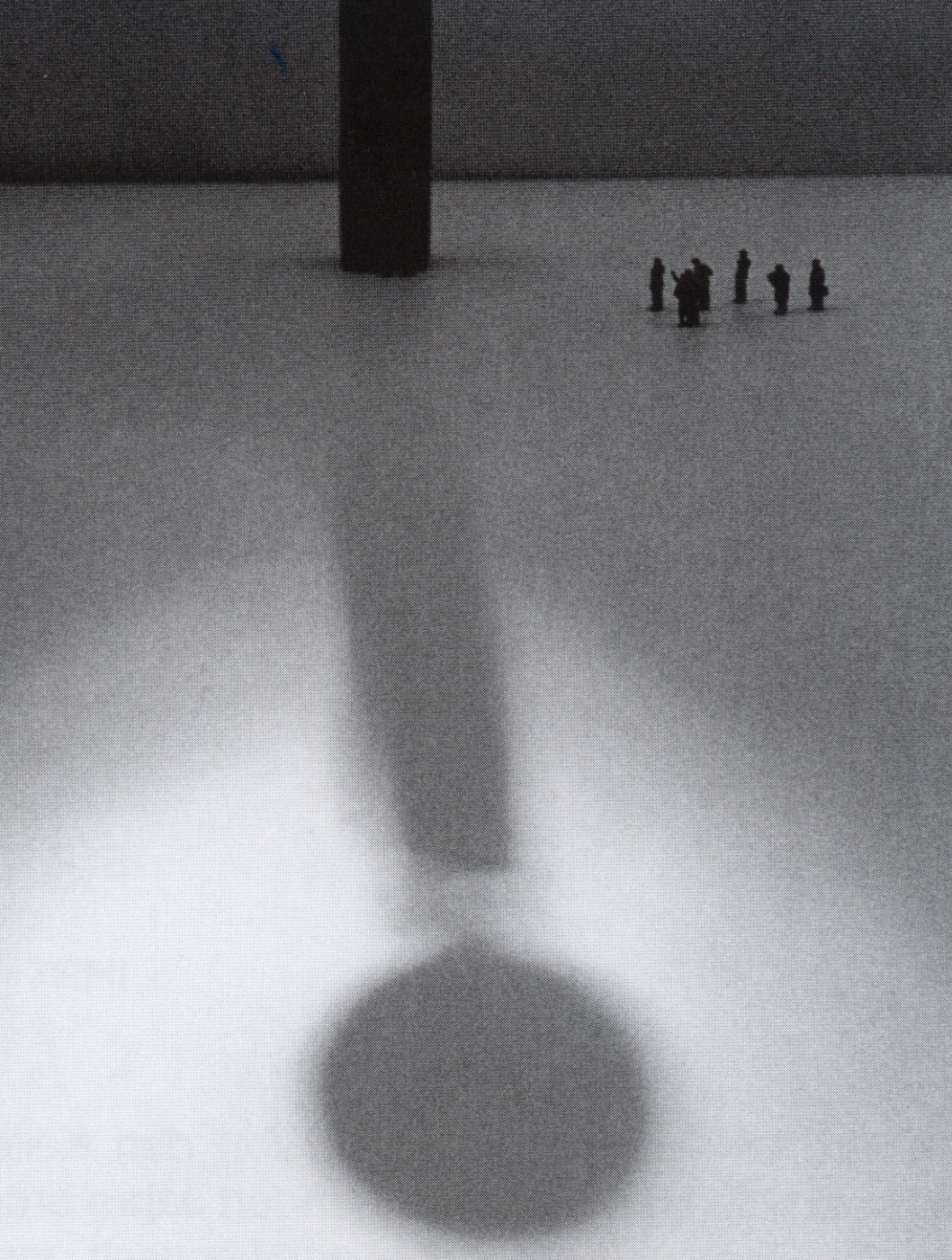

The monument throws off a shadow in the form of an exclamation mark. (!)

The orb symbolises evil, its perfect aesthetic appears aloof. Even, smooth, shinny, an inner pressure seems to prevail. The surface is taut, everything rolls off it. It is hard to grasp. The orb is the expression of perfection; beautiful people, polished boots, perfectly organised events, convincing propaganda….

Granite represents the “everlasting values” which have ultimately become graves…

Black the colour of darkness, the SS-uniforms, death….

The weight, several tonnes, embodies the burden which the descendants must bear.

The wedge represents the present; reason, conscience, civil courage….

The little wedge can restrain the mass, because the mass is still. Should the mass however begin to roll, it can no longer be halted….

The tall, thin column represents the victims, who bore the weight of evil. The raw concrete, built together with an endless number of little stones, contrasts with the smooth ball. Contrary to Atlas, who in Greek mythology alone carries the world, we must recognise that only together with many- millions of people – can this burden be born.

And so that the individual in this mass is not forgotten, each side of the column bears the

I – MINE

YOU – YOUR‘S

HE, SHE, IT – HIS/HERS

YOU (pl.) – YOURS‘

THEY – THEIR‘S

This monument is intended to be an active monument: 100 wedges representing the next 100 years will be produced. Each year, on a specific day, the wedge will be exchanged so that the memory remains alive. The replaced wedge should be given to a person or institution which has demonstrated resistance to evil.

The wedges, stored in a suitable place, will, year for year, be fewer in number. The wedges will be like a ticking clock, alluding to the already begun countdown; evil is omnipresent.

We must be on our guard!

Gábor Török, Frankfurt/Main, in June 1997